History is rich with stories of rulers and colonizers grappling with the challenge of maintaining control over diverse and often divided populations.

A recurring strategy has been to empower a specific group—frequently an ethnic or religious minority—by granting them privileges, political power, or preferential positions. While this approach can provide short-term stability, it often leaves behind a legacy of mistrust, division, and violence. Over time, these fractures have erupted into some of history’s most devastating conflicts.

This article explores this historical pattern through key examples, analyzes the dynamics at play, and reflects on lessons that resonate even today.

Rwanda: Tutsi Privilege and Genocide

During Belgian colonial rule, the Tutsi minority in Rwanda was elevated above the Hutu majority. This elevation was deliberate: the Belgians granted Tutsis access to education, administrative roles, and political power, casting them as natural leaders under a fabricated racial hierarchy. For the Belgians, the Tutsis were a useful intermediary to enforce colonial policies.

However, this system came at a cost. The Hutus, denied similar opportunities, grew resentful. After Rwanda gained independence in 1962, the narrative of Tutsi privilege continued to haunt the country. The Hutus saw the Tutsis not only as collaborators with colonial oppressors but as symbols of their own exclusion.

This resentment exploded in 1994 during the Rwandan Genocide, when Hutu extremists orchestrated a mass killing of approximately 800,000 Tutsis in just 100 days. This tragedy is a stark reminder of how systemic favoritism can entrench divisions that, when inflamed, lead to unimaginable atrocities.

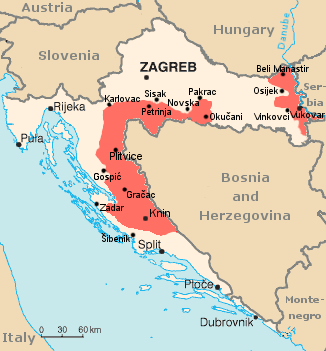

Krajina Serbs: Austro-Hungarian Border Guards and Ethnic Cleansing

In the Military Frontier of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Serbs were granted land and privileges in exchange for defending the empire’s borderlands against Ottoman incursions. This arrangement benefited the empire: the Krajina Serbs became loyal "border guards," ensuring stability in a turbulent region.

But for the neighboring Croatian population, these privileges were a source of frustration and resentment. Over time, the Serbs' special status created divisions that were easily exploited in moments of political upheaval.

During the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, nationalist leaders reignited these historical grievances, portraying the Krajina Serbs as outsiders and threats. The result was ethnic cleansing, mass displacement, and atrocities that tore the region apart. What began as an imperial strategy for stability became a centuries-long source of interethnic conflict.

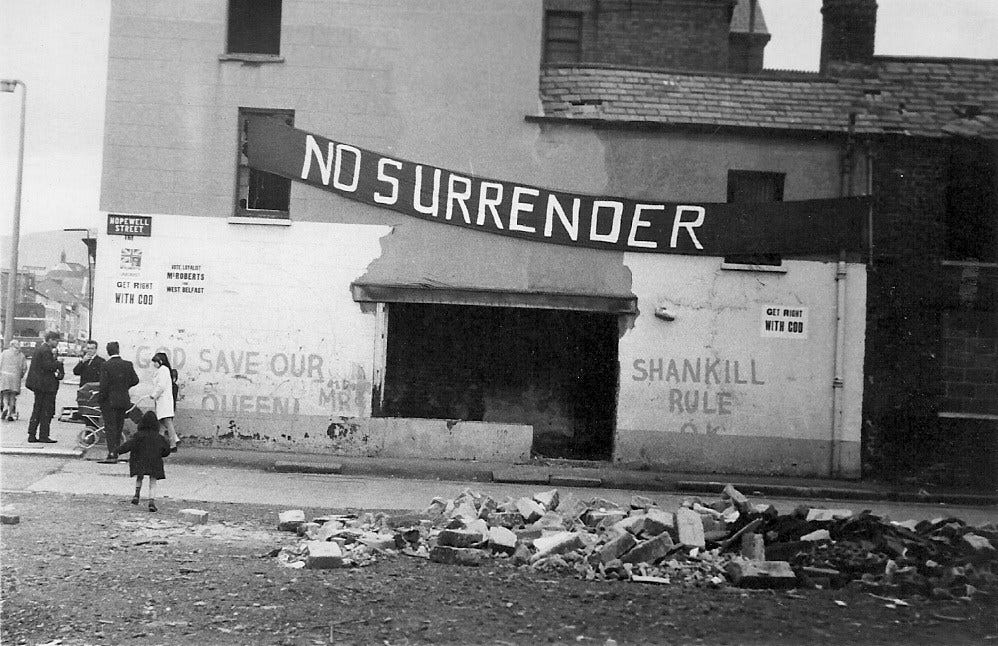

Northern Ireland: The Protestant Scots and Sectarian Divisions

In the 17th century, the British Crown initiated the Plantation of Ulster, settling Protestant Scots and English families in predominantly Catholic Ireland. These settlers were granted land, political power, and economic advantages, ensuring a loyalist base in a region long viewed as rebellious.

For the Catholic majority, this policy was deeply alienating. Their land was taken, and their voices were marginalized, while the Protestant settlers were given disproportionate authority. Over centuries, these divisions hardened into sectarian animosity.

By the late 20th century, these historical grievances culminated in The Troubles, a brutal conflict characterized by bombings, assassinations, and political violence. The British empowerment of Protestants fostered not only immediate control but also a legacy of resentment, with each side viewing the other through a lens of historical grievance. Northern Ireland remains a case study in how preferential treatment of one group can cement deep societal divides.

Bosniaks in the Balkans: Ottoman Favoritism and Ethnic Violence

Under Ottoman rule, the empire strategically favored Bosniaks (Slavic Muslims), granting them administrative roles, land ownership, and military privileges. For the Ottomans, this was a pragmatic strategy to secure loyalty in a predominantly Christian region.

However, this favoritism alienated Christian Serbs and Croats, who viewed the Bosniaks as collaborators with a foreign empire. As the Ottoman Empire weakened in the 19th and 20th centuries, these grievances intensified.

During the Yugoslav Wars, historical resentments toward Bosniaks were weaponized, leading to atrocities such as the Srebrenica Massacre, in which over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were killed. Ottoman policies, long abandoned, had left scars that nationalist rhetoric turned into violence.

Shared Patterns Across Cases

Despite differences in geography, culture, and historical periods, these cases reveal striking similarities:

Short-Term Control vs. Long-Term Stability: Empowering a minority group often secures temporary loyalty but at the expense of societal cohesion.

Entrenched Privilege and Resentment: When one group is visibly favored over others, resentment festers, creating fertile ground for future conflict.

Historical Narratives and Exploitation: Political leaders frequently exploit historical grievances, using them to mobilize violence or consolidate power.

Other Examples of the Pattern

This dynamic is not unique to the cases discussed above. Similar patterns have unfolded across history:

Iraq under Saddam Hussein: The Sunni minority enjoyed disproportionate power, alienating the Shi’a majority and contributing to sectarian violence after Saddam’s fall.

Myanmar’s Rohingya Crisis: British colonial policies that favored the Rohingya created resentment among Myanmar’s Buddhist majority, fueling modern atrocities.

India under British Rule: The British divide-and-rule strategy deepened Hindu-Muslim tensions, culminating in the violence of Partition in 1947.

Lessons from History

Inclusive Governance: Rulers must prioritize policies that foster inclusion and equality, rather than favoring one group over others. Empowerment should uplift entire communities, not deepen divides.

Addressing Historical Grievances: Societies emerging from such divisions must confront historical grievances through reconciliation processes, truth commissions, and equitable reforms.

Preventing Exploitation of Divisions: Modern leaders must avoid weaponizing historical grievances for political gain, recognizing the long-term risks of stoking intergroup hostility.

Conclusion

History offers a stark warning about the dangers of empowering one group at the expense of another. While this strategy might seem pragmatic in the moment, it often leaves a legacy of mistrust, division, and violence. To build stable, cohesive societies, leaders must learn from these examples and prioritize governance models that emphasize inclusion and reconciliation.

A Note on Complexity

It’s worth noting that the conflicts described here are deeply complex. While this article highlights one recurring dynamic, these examples are shaped by a web of historical, cultural, and political factors. Simplification is necessary to focus on the broader pattern, but the intricacies of each case merit deeper exploration.

That said, the central lesson remains clear: when rulers divide, societies fracture.

☕️ If you enjoy this analysis, please consider supporting my work at buymeacoffee.com/terjehelland, or at PayPal.

Your support motivates me to keep informing and engaging.

Thank you! 🙏